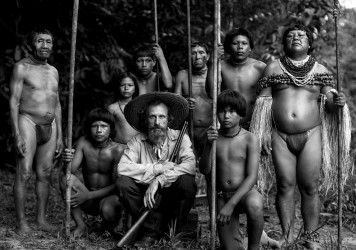

James Gray channels Joseph Conrad in this immaculately-crafted but lacklustre epic.

As recounted by David Grann in his devourable 2009 non-fiction bestseller, the story of Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett is one of the great unsolved mysteries in the annals of exploration. Single-minded in his pursuit of an elusive “lost” civilisation, and at odds with contemporary scientific reasoning, Fawcett led a three-man team deep into uncharted Amazon territory before disappearing without a trace in 1925.

Grann frames the story as a mystery, positioning himself as the latest in a long line of what today’s Royal Geographic Society dubs the “Fawcett freaks” – amateur adventurers who succumbed to the lure of an obsession that led them along a path to tragedy.

Breaking with Grann’s structural device, James Gray’s screen adaptation sets out Fawcett’s tale in straightforward biographical terms. He forgoes the metaphorical allusions found in the erstwhile jungle jollies of Werner Herzog’s journey into the abyss, Aguirre, the Wrath of God, or 2015’s similar, superlative Embrace of the Serpent, by Ciro Guerra. Gray has proven himself a master matchmaker of form and content. He amped up stylistic licks for the genre-inflected We Own the Night, then tempered them in the face of Two Lovers’ quieter emotional melodrama. The Lost City of Z sees him operating in a broader classical mode, both narratively and formally.

The setting alone can’t help but invoke the spirit of Joseph Conrad (the author famed for his 1899 novel, ‘Heart of Darkness’), but beyond such superficial touchstones, Gray’s films have all been interested in that ubiquitous, Conradian question of self-definition. A subtle, incisive cultural ethnographer, Gray has long established micro-communities and set them against a broader social canvas, allowing his black sheep to roam free. The notion of ‘home’ is central to Gray’s back catalogue, and affords Z its primary thematic conflict, albeit one painted in overtly literal terms.

Fawcett’s wife, Nina (Sienna Miller), proves to be another of Gray’s female characters whose fate is defined by their male counterpart. The film’s ending may belong to her – a magnificent final shot evokes that of the director’s previous film, The Immigrant, as she turns her back on her own reflection to step into her missing husband’s quest – but Gray’s script (“I’m an independent woman!”) does her few favours throughout.

Miller delivers a fine performance nonetheless, not least in her closing monologue, even if she can’t quite escape her essential modernity. It’s a problem cripplingly shared by Charlie Hunnam’s Fawcett, a role crying out for a degree of psychological complexity that is not provided either by Gray or his lead. If Grann’s Fawcett is intended to be taken as definitive, Gray’s approach is revisionist, to simplistically diminishing returns.

The Lost City of Z’s technical credentials are unimpeachable and serve as the primary means of engagement. Darius Khondji’s cinematography is nothing short of god-level, and Gray continues to prove himself a stellar soundscape designer. Yet for all the set-pieces he directs the hell out of – an opening hunt; a piranha attack – it’s only in its elliptical final throes that the film eclipses its surface pleasures, as the eponymous city shifts from narrative goal to vaporous MacGuffin.

Published 21 Mar 2017

James Gray goes epic.

A work of eyeball-melting craftsmanship.

Beautiful, but skin-deep.

Hopes were sky high for James Gray’s lavish NY period drama, but this one left us cold.

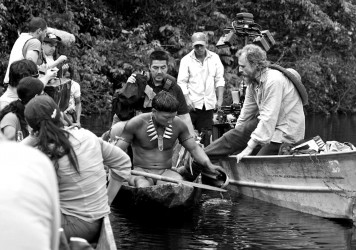

Ciro Guerra’s film is a stark reminder of the destructive nature of European colonialism.

Embrace of the Serpent director Ciro Guerra on the logistical and spiritual challenge of shooting in a rainforest.