Ciro Guerra’s psychedelic Amazonian odyssey is one of year’s most potent and strikingly original films.

Colonialism and memory serve as the twin forces steadily erasing an entire cultural heritage on this slow-burn journey down the Amazon. It’s a film pregnant with mystical symbolism. And its complex structure ends up being the key to deciphering its meaning. Director Ciro Guerra weaves together two narratives, one from the turn of the 20th century, the other taking place some 40 years later; each is a fictionalised account of a search by a pair of real-life German ethnographers for the film’s elusive MacGuffin, the yakruna plant, said to possess hallucinogenic properties.

Uniting the two narrative strands is a character slowly revealed as our guide, Karamakate, seemingly the last surviving member of the Cohiuano tribe. Karamakate is played by two actors – as a young and older man. His presence bridges the two eras with an unreliable subjectivity. He looks down on the western white men in his company, failing to differentiate between them. He is what he refers to as a “Chullachaqui,” a spectre of his former self. “We all have one,” he says. “It looks like you, but is empty, hollow, a ghost without time.”

With the help of screenwriter Jacques Toulemonde Vidal, Guerra crafts a rich thematic allegory on the effects of colonialism. It takes the form of a serpentine dance through time, sounding a series of echoes beyond the immediate horrors borne of its Conradian heart of darkness. And horrors there are plenty, not least in scenes at an orphanage populated by sadistic missionaries and a Colonel Kurtz-like demagogue in each respective timeframe. Guerra’s movement between eras (in one stunning instance, without the use of a cut) exposes the festering wounds of colonialism.

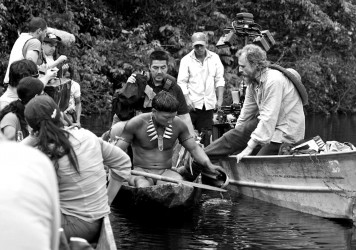

Director Ciro Guerra on the challenges of making a movie in a rainforestDavid Gallego’s rich, monochrome Super 35 cinematography accentuates the oppressive and the beautiful. Open spaces take on a claustrophobic quality, heightened by Karamakate’s increasing disconnection. If, on occasion, the screenplay spells out its thematic motifs, as in an episode with a missing compass (“You cannot forbid them to learn!”) or a trading of creation myths (featuring Haydn’s, um, ‘Creation’), Guerra continually leads with his images. An extraordinary opening credit sequence of a snake feasting on its young is impossibly bettered by a late, subtextually-weighted jaguar versus serpent attack.

Yet what takes hold long after the credits have rolled is a final sequence at the end of the expedition. The discovery of the last yakruna plant, shared with the later explorer, explodes into a metaphysical kaleidoscope of colour, its mind-expanding irruptions channelling the stargate set piece at the end of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Where that film’s wormhole charted a course through the folded fabric of space to question the affects of the extra-on the terrestrial, Guerra pulls off a coup that bears the weight of comparison well.

Punching a hole between its twin points in time, the film lays bare the destructive force of modern man on his environment. Nature itself finally offers up a vision of enlightenment, albeit one that’s too late for salvation.

Published 8 Jun 2016

Ciro Guerra’s first two features were terrific.

This was never going to win the Oscar.

An exquisitely rendered study of colonialism, memory and cultural erasure.

Themes of social displacement and isolation will be explored in the documentary series ‘Frames of Representation’.

A jaw-dropping spectacle and brain-melting existential nightmare, Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam opus is touched by genius.

Embrace of the Serpent director Ciro Guerra on the logistical and spiritual challenge of shooting in a rainforest.