A bittersweet road movie about the joy and sadness of ageing directed by the great Alexander Payne.

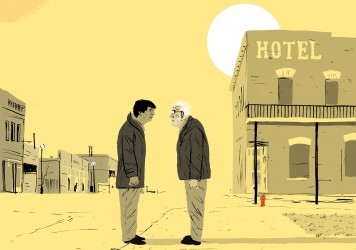

Alexander Payne’s new movie shares its name with one of Bruce Springsteen’s greatest albums, and both share a primitive sensibility in which everything bar the essential is pruned back to its roots. And just as the Boss’s four-track opus played out in the mind like some monochrome bordertown noir, so does this arrive in glowing, washed out black-and-white.

The decision to film Nebraska in black and white is fitting — symbolising the two-tone simplicity of life in the American midwest while also imbuing the people and landscape with a mythic quality. The film works as a companion piece to his doleful Polynesian caper, The Descendants, in that both films follow middle-aged men who have been touched by the possible death of a close family member, and examine their subsequent efforts to instigate some kind of short-order Karmic realignment.

The film starts of slowly and, frankly, quite badly. It’s not just the male melancholy set-up which feels like Payne self-parody, but the performances are stilted and affected. Payne’s patented dry humour, too, seldom hits home. Will Forte’s Davey is a bespoke hi-fi salesman who’s getting consistently irked by his father’s monomaniacal tendency to wander off down the highway with the intention of reaching Lincoln, Nebraska in order to cash in a junk mail prize draw ticket which he believes insures him the princely sum of $1 million. Woody — beautifully played by ’70s indie Hollywood godhead Bruce Dern — won’t take no for an answer, and so Davey decides to drive him to Lincoln so he can see the sham with his own eyes.

It’s when Davey and Woody hit the road that the film begins to find its feet. And it’s when the pair reach the town of Hawthorne that the film begins to really cook and beautifully consolidate its delicate themes. It’s a place where Woody spent much of his formative life as the town mechanic and where many members of his extended and semi-estranged family still reside. Thinking that this black sheep is sitting on a fortune, it’s not long before they’re calling in all those financial favours from the past.

Though the film deals with Davey’s attempts to sate what may be one of his father’s final desires, the film is great when examining the tragic stories and failed relationships that are sadly lost in the space between generations. It may sound corny, but Davey’s belated, often second-hand discovery of his father’s youthful indiscretions is handled with admirable sensitivity and poise.

And while the film may appear to be a bittersweet dissection of a man running off the final vapours of life, it also addresses the death of old American. These sand-blasted ghost towns that Payne knows so well are also presented as being on the cusp of obscurity, as the letters have fallen off all the signs and vacant lots fill up the downtown strip.

For the most part, this is a lovely comedy of regret and remorse that deals with how the prospect of death is viewed by both young and old. At its best, it shows Payne’s capacity for a melancholic humanism that captures a consummate mixture of tragedy and comedy.

Published 13 Dec 2013

A new Alexander Payne film is a big deal. One with Bruce Dern in the lead is essential.

A shaky start, but it blossoms beautifully.

A bigger, deeper film that it initially appears. Dern’s performance is a delight.

A confident return to the feature filmmaking fold from Alexander Payne featuring a champagne turn from George Clooney.

The American director of The Descendants talks about finding paradise in his own backyard.

By Ed Gibbs

Alexander Payne’s gentle satire has a point to make about the state of the union – and the future of planet Earth.