Orson Welles is some kind of a man in this grisly, ultra-melancholic border-town noir from 1958.

To paraphrase François Truffaut’s observations on Touch of Evil, Orson Welles created a character in corpulent Hank Quinlan who is so unrepentantly revolting that we end up falling in love with him. He also created a character in Mike Vargas (Charlton Heston) – a dude who shoots so straight it hurts – that we end up despising him.

It’s a film which flips concepts of heroism and villainy on their respective heads, devious conduct is normalised in a world plagued by cruelty and injustice. Working on baseless hunches, sending people to the gallows with a certitude that comes nowhere near being beyond reasonable doubt, is how this crooked world turns. “He was some kind of a man… What does it matter what you say about people?” is the utterly devastating final line spoken by cigarillo-puffing, pianola-playing clairvoyant Tana (Marlene Dietrich), sealing this notion that people are too complex to be straight-jacketed as the products of their banal earthly actions.

Welles came aboard this film by accident, rewrote it from scratch and then had the final cut taken from him. Even for the late ’50s, when you had people like Samuel Fuller and Nicolas Ray making markedly weird movies, or at least weird riffs on normal movies, Touch of Evil takes things to the baroque next level. The giddy constellation of eccentric side players and slum-like locations coalesce to form a story that often comes across as contrived. But it’s only by its tremendous, surreal climax that you realise that this is pure character study and not some wantonly outlandish noir- thriller in which everything ties up in a neat bow.

It’s a film which pits intuitive man against pragmatic man, and ends up by deducing that both lifestyles have their relative strengths and weaknesses. Like the bomb that’s lobbed in the boot of the soft-top car in its opening scene, Touch Of Evil is a film where we can hear the faint sound of ticking in our heads, but don’t realise what the problem is before it’s far too late.

Published 10 Jul 2015

Orson Welles’ mangled masterwork is back in town.

Madness has never looked this soulful.

“An hour ago, Rudy Linnekar had this town in his pocket. Now you could strain him through a sieve.”

By Adam Cook

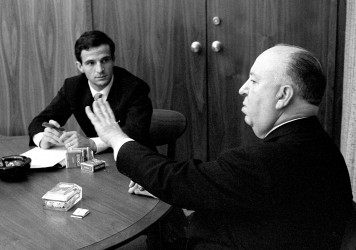

Two grand masters come head to head in this insightful documentary from film critic Kent Jones.

The moral minefield of Carol Reed’s The Third Man insures its place in the pantheon of greats.

Jean-Luc Godard’s masterpiece stands the test of time, still managing to feel incredibly fresh and exciting.