In tandem with a full Scorsese retrospective, this beloved meatball opera is served up once more.

Let’s pour one out for Ray Liotta, the last man (barely) standing in Martin Scorsese’s roistering gangland firework display, Goodfellas. Glancing over his extensive and varied career within the movie business, this iconic title remains a lofty if precarious peak. It’s akin to the moment where his twinkle eyed mafioso-in-waiting, Henry Hill, is ushered through to the bustling inner sanctum of an exclusive lounge club. A fiancé-to-be is hooked on his arm, and he is planted front and centre by kind insistence of the toadying management and a silky-smooth extended tracking shot.

This is the moment where he gets the special favours, and all his peers are forced to look on as he sashays through the cigar smoke and right into their eye-line. With all due respect to this unique leading man, his career after Goodfellas saw him drift on a gentle downward trajectory which, for a film of this stature, is no big thing. But maybe this is the film that cursed him, that opened uninviting doorways to roles in quick fix, substance-neutral gangster flicks and VHS shelf-filling action craptaculars. When a supporting role in a Guy Ritchie film can be considered a late career highlight, then we most certainly have a problem.

Goodfellas is a terrifying film because, like much of Scorsese’s best work, it is about the lives of avuncular psychopaths, and pretty-boy Liotta brilliantly encapsulates that fetid contradiction. Of all the murderous thugs on show, he is by far the kindest, the one you’d like to see looking down on you as he boots your face into a pulp. Here is a man whose first experience of true love is not from a stolen front-seat kiss, it’s the moment he cold-cocks a romantic rival in a suburban driveway, the victim’s effete pals looking on through arcs of blood.

To see Liotta in a film now is like a trigger warning – he might initially come across as sweetness and light, but it’s only a matter of time before he starts screeching, sweating and staving skulls. That stigma is unhelpful. Unadorned kindness can never be part of his repertoire because of who he is and his past professional associations. He is the boy next door who kills people. That he has made a life from this unique set of talents is certainly laudable, but maybe he’s an actor whose best was revealed too soon. Yet he is great in Goodfellas because of the wingmen who help him. It’s down to a well oiled and minutely balanced ensemble of actors. They draw the best from him.

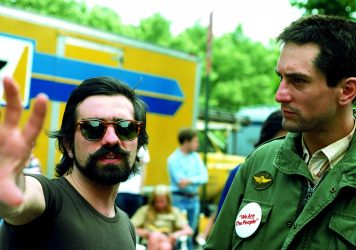

Goodfellas is strange in that you think Robert De Niro would be the film’s focal point, but his Jimmy, a paranoiac charmer who only laughs as others suffer, simmers in the wings without ever really boiling over. It’s as if he knows he’s had his shot at the title with Raging Bull, Taxi Driver, The King of Comedy, et al, and he’s allowing the new kid a chance. De Niro’s performance is muted and unassuming, maybe even a little one-note (“Pay me my fuckin’ money!” etc, etc), but this could be viewed as an actorly gesture, allowing Liotta his long-awaited dues, understanding that while he is a facilitator for the drama, this is not his story.

Joe Pesci, meanwhile, reignites the size doesn’t matter credo from the days when James Cagney and Edward G Robinson flew the flag for diminutive badassdom. His performance is extrovert and astounding, occasionally verging on the surreal. Whether it’s Pesci’s natural body movement or something affected for the role, he brings a balletic quality to the regular beatings he administers.

There’s a crisp quickness to the way he unsheathes his firearm and shoots unfortunate drink-forgetting lackey, Spider. And too, the manner in which his short arms flails to help him keep balance as he’s kicking Frank Vincent’s Billy Batts to death in a dive bar. Yet where Di Nero goes soft and Pesci goes hard, they part ways to allow Liotta that comfortable seat, right at the front and centre. Maybe a grand second act is yet to come, and some upstart maverick will pluck him from obscurity and gift him with the role of a lifetime.

As it stands, Liotta is out there in the unknown, a lost schnook with his bowl of noodles and ketchup. Goodfellas stands testament to the fact that someone would do well to bring him in from the cold.

Published 20 Jan 2017

Needs no introduction.

If it ever crops up on the TV, you have to watch to the end.

As a re-release, it’s not the most exciting choice within Scorsese’s remarkable back catalogue.

A comprehensive guide to the directing credits of this great American auteur, from Mean Streets to The King of Comedy to Killers of the Flower Moon.

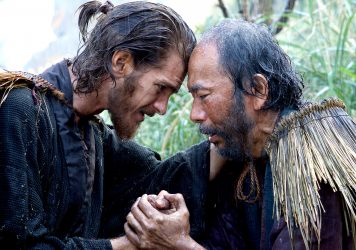

Scorsese’s monolithic passion project finally arrives, and it’s a ripped straight from his spiritually devout heart.

An incredible video essay looks at divine presence in the work of this American master.