Ever wondered why Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto?

Imagine, if you will, a traditional comic book origin story, the type that seems to be dropped into our multiplexes on a near-weekly basis. Now imagine that, instead of some wide-eyed, spud-faced nerd learning to wield his newfound super-human abilities, the heroes in question are actually a pair of pasty, 19th century social scientists and their costumes for warfare comprise of knee-length grey overcoats, pillbox hats and mighty beards.

The Young Karl Marx is a well turned-out historical biography of the stern, logical, impassioned Karl Marx (August Diehl) which explores his tag-team partnership with politically simpatico German philosopher, Fredrich Engles (Stefan Konarske). The story’s ironic “saving the world” moment is the eventual writing of The Communist Manifesto, and director Raoul Peck takes us on a journey through hostelries, meeting halls and dust-filled attics to show how these two iconoclasts were able to divert the course of history with little more than a quill and some radical thinking.

It’s a film which goes deep on the history of discourse as much as it does the subjects themselves. Pascal Bonitzer and Peck’s script doesn’t skimp on the weighty philosophical prose, the expression of ideas and how those ideas evolve alongside the changing social and economic climate. Just as revolutionary communism demands the right set of conditions, so too does the mere utterance that a new political doctrine is afoot which contains the instructions and reasoning behind the eventual dismantling of the capitalist system.

As entertainment, you really must have a very high tolerance for shots of people talking in rooms, as the runtime is filled out with a lot of intense chatter and protracted speechifying. If anything, the film falters as it offers the least radical visual rendering possible of a story about two people whose lives were fuelled by the prospect of smashing up the tired old frameworks. There are no memorable shots in the film and Peck seldom attempts to tell the story, or at least exemplify its themes, through visual means. It actually looks a lot like it was made to be consumed on television.

Vicky Krieps, last seen wowing in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread, delivers a low key turn here as Marx’s doting wife (and intellectual equal) Jenny, while the great Olivier Gourmet brings a sense of weary gravitas as his French mentor, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Initially, it’s very tough going and self-serious, and when a tangible drama eventually rears its head in the closing act (how the pair intellectually usurp the clandestine revolutionary organisation The League of the Just), it’s too little too late. But, the people who dig this will know straight away.

Published 5 May 2018

That title doesn’t leave much room for ambiguity.

Does exactly what it says on the tin. A dream film for left wing activists.

A slog, but a worthwhile one.

By Sam Thompson

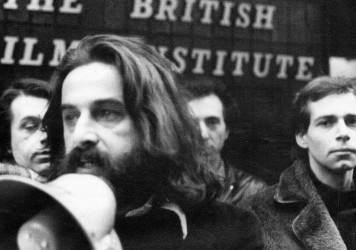

Radical socialist filmmaker Marc Karlin emerged as a key counterculture figure in the 1970s and ’80s.

The star of Paul Thomas Anderson’s beguiling latest explains how she was able to square up with Daniel Day-Lewis.

By Matthew Eng

James Baldwin reclaims the spotlight in Raoul Peck’s magnificent film essay.