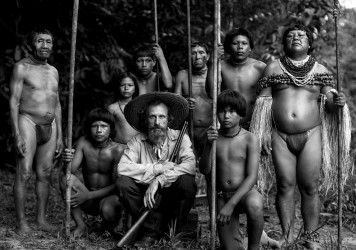

Embrace of the Serpent director Ciro Guerra returns with a full-bore narco saga set in rural Colombia.

It’s a tale as old as the Hollywood hills: young Colombian upstart marries into a tribal clan by securing a dowry through his drug trafficking payola. But once he’s tasted the good times, it’s hard to resist taking another little bite of the pie. And so the blocks of cash roll in, the bad eggs reveal themselves and roll out, and the dream of a rich cash crop and inter-tribal peace is scuppered by a swathe of unnecessary humiliations and brutal honour slayings.

Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra’s Birds of Passage is a rags-to-riches-to-rags narco saga we’ve seen a thousand time before. Yet it offers the rare chance of monitoring these timeworn machinations from the vantage of a tinpot cartel operation rather than the greedy, gak-snorting yanks. Beginning in the mid ’60s and climaxing in the early ’80s, this true life tale offers a more laconic, less glossy take on the minutiae of illegal trading than its US counterparts, even though its ‘crime doesn’t pay’ message rings out just as loud and clear.

The film recalls Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, in that it explores the disparity between an ancient code of ethics and the grubby minutiae of modern criminal endeavour. Raphayet (Jose Acosta) claps his eyes on Zaida (Natalia Reyes) and enters into a bizarre public mating ritual in a bid for her hand. She peacocks around a circle with a coloured shawl fanned above her head, while he nimbly skips and hops in front of her.

Her imperious, unsmiling mother (Carmiña Martinez) takes the task of preserving the family bloodline extremely seriously, and clearly sees something wayward in her enigmatic, blank-faced son-in-law-to-be. Visions come to her in lucid dreams, and she also receives signs from nature in the form of visiting birds and insects. At one point, she correctly predicts an oncoming plague.

It’s a bit of a strange film all-told, in that it perhaps rides for a little too long on the idea of a taking a highly conventional plot and transposing to this unique setting. Even though the film deals with characters who life and die by the dictates of tribal diplomacy, it ends up suggesting that it doesn’t take much to bend the rules for the sake of a quick buck. As such, we’re eventually left with warring factions who have tossed their ancestors to the curb, exemplified in a sequence where a family member’s corpse is exhumed from the grave and his bones polished, with the same graves shown again later, now containing crates of guns where the bodies once were.

As a critique of capitalism, it couldn’t be more blunt, but there’s something satisfyingly absurd about seeing these earthy folks ride across the arid flats in giant 4x4s and eventually upgrade their decrepit wooden shack to a gaudy stucco mansion. Strangely, the directors have told the story in a way that makes it feel like it’s happening in the present day, mainly due to a few modern production details and some stiff performances from the small US contingent of the cast.

The film rattles along pleasantly without ever really tipping over the edge, or using the setting to say something new about the hazards of the drug trade. No one scene or image really lodges itself in the mind or stands out, making it feel like an intriguing albeit superficial curiosity rather than a sweeping epic with any real emotional depth.

Published 9 May 2018

By Matt Thrift

Ciro Guerra’s psychedelic Amazonian odyssey is one of year’s most potent and strikingly original films.

Asghar Farhadi returns to Cannes with a slowburn domestic drama about secrets, lies and unsettled scores.

Ciro Guerra’s film is a stark reminder of the destructive nature of European colonialism.